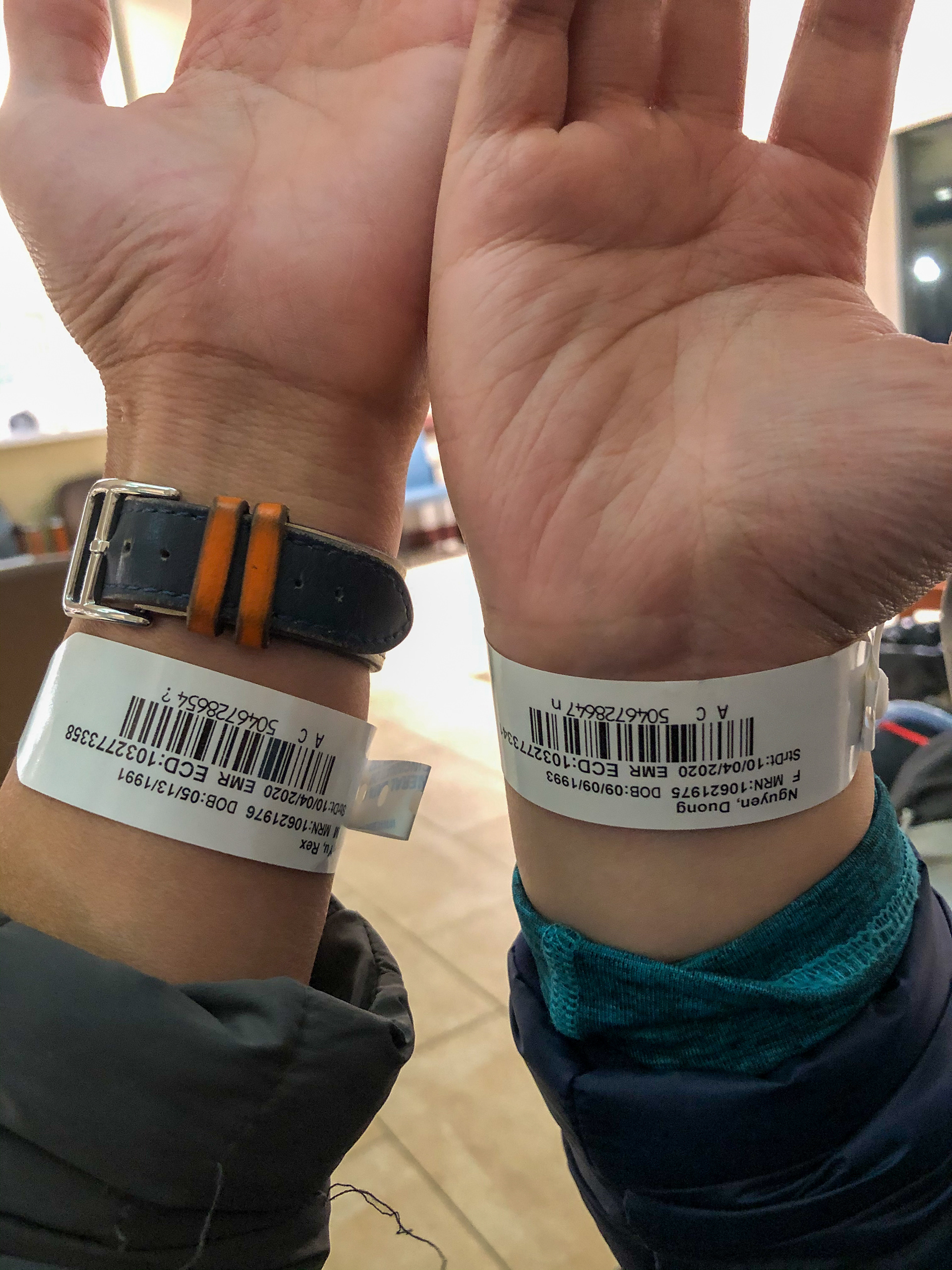

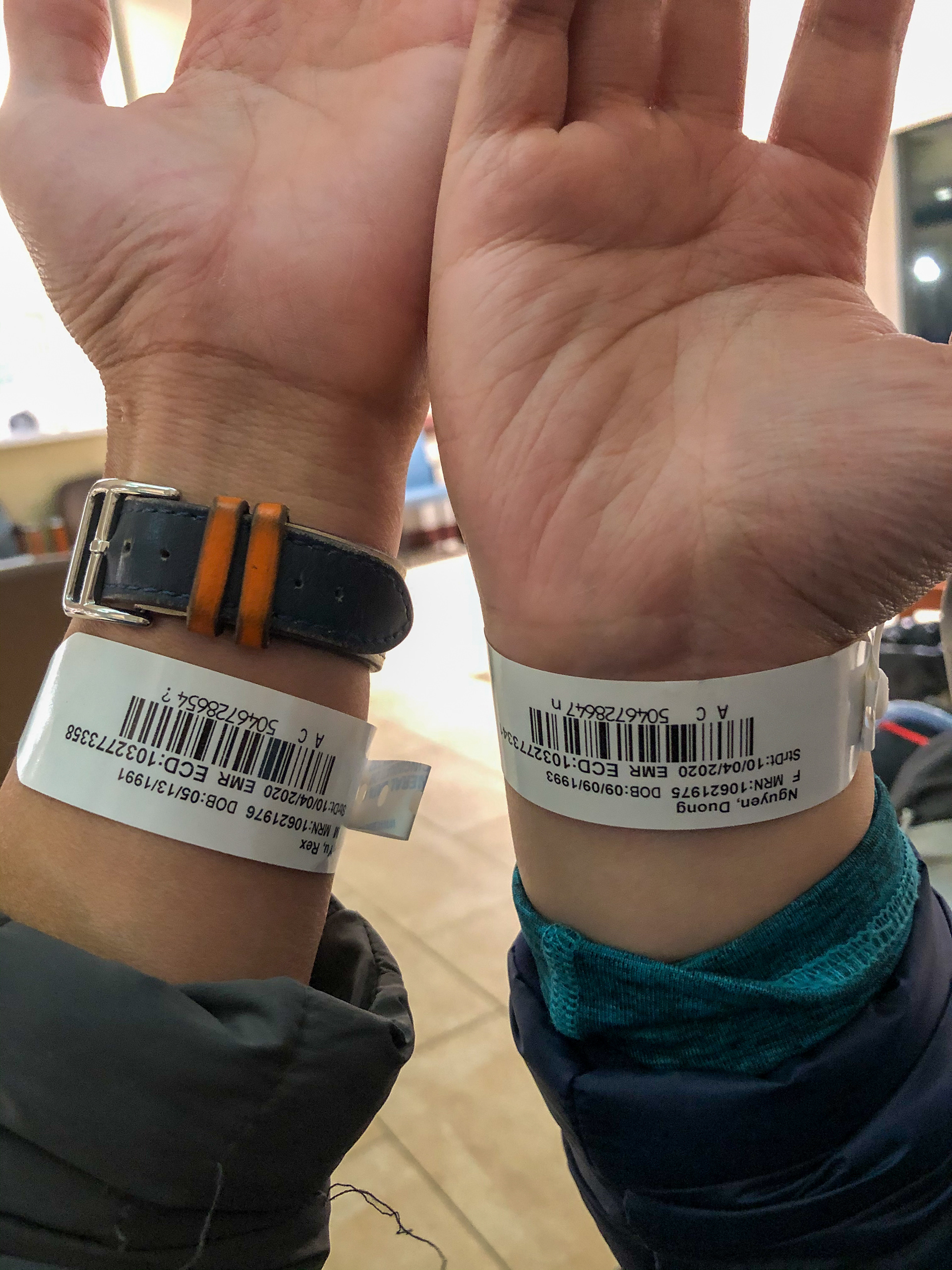

“Second in height only to Mount Rainier statewide, 12,276-foot Mount Adams looms over at least 10 impressive glaciers and wilderness of forested slopes and subalpine meadows. The huge volcanic bulk of the mountain takes up a considerable portion of the wilderness and rises to its only peak. As many as 25 climbing routes, from nontechnical to technically challenging, provide access to this very popular summit. Elevation gain is approximately 7,000 feet.” As we have accomplished more backpacking and advanced hiking, we have been looking for something different, something slightly more challenging. In the past 3 months, we had conservatively chosen our hiking places as we recognized that mountain is not what we can underestimate. Yet, this time we decided to be bold and attempt our very first mountaineering to the summit of this forgotten giant – Mt. Adams. In fact, it was our second attempt. About a week ago, we attempted this mountain over two days, beginning our ascent from the trailhead and heading to Lunch Counter for the first evening. We planned to reach the summit with an early wake-up call on the second day, yet the snowstorm collapsed our tent and forced us to retreat before dawn on Sunday. This time, we planned to day-hike to the summit from the very bottom without camping overnight. The weather was definitely on our side this time; there was soft wind, no rain, and no snow. The temperature at the trailhead was around 40*F on Friday night, and the moon was like a spotlight in the sky guiding night climbers the path to home, or… away from home. We woke up at 12:30 at midnight and got our supply and gears ready. At 2 o’clock in the morning, when everything still remained asleep, we moved our steps to the trail (5,555 ft). The only sound we heard from the forest was silence, which made our breaths noticeably loud and noisy. We followed along with the South Climb trail in the moonlight shadow until we started to climb up after crossing Morrison Creek. New snow from last weekend had all gone before Lunch Counter. Old ice fields were still present intermittently. We put on our microspikes and turned off our flashlight as the reflection of moonlight on the ice was bright enough to show all the footsteps from previous climbers. We arrived at the high campsite, the Lunch Counter (9,200 ft), at 6:30 a.m. when the sky had slightly appeared the violet color with a lovely pink brush. The beautiful scenery of the Cascade Range was painted with many layers of red, violet, rose, and gold colors by the sunrise over merely 30 minutes. We sat in one stone-made windbreaker and cooked for our first meal with fresh shrimps (yes, I carried fresh shrimps and pork this time), and prepared ourselves for the summit attempt. The gigantic peak in front of us is Pikers Peak, also known as False Summit. It is roughly one mile from Lunch Counter on an elevation of 11,500 feet. Climbers won’t be able to see the true summit until climbing over False Summit as Mt. Adams Summit was hidden behind it. The snowfield was enormously wide, yet dangerously steep with a 45 to 60-degree angle. Every single step required extra adrenaline circulating in the body. As soon as we were climbing over the 10,000-foot mark, acute mountain sickness (AMS) hit us. We suddenly experienced headaches, dizziness, and mild nausea. Our hearts were pumping hard and our breaths become heavier due to slightly lower saturation of blood oxygen. AMS was actually expected from our previous experience in Camp Muir. We took Meclizine 25 mg and Ibuprofen 400 mg to ease the symptoms of AMS. We slowed down our pace to allow our bodies to adjust themselves. It must be on record our longest one mile ever, which took us 3 hours to reach Pikers Peak. There was a fair amount of flat space for climbers to actually sit and rest on Pikers Peak. On an elevation of 11,500 feet, we were facing south and saw the whole Cascade Range in front of us, which included Mt. Hood (11,250 ft) in the central of our view and Mt. Saint Helens stratovolcano on our right-hand (western) side. Fortunately, the smoke from the California wildfire did not ruin the spectacular views of mountain scenery too much. The view on Pikers Peak was not 365-degree because behind us there was a big hump blocking the northern view. The true summit is on top of that big hump, and the highness of Mt. Rainer is right behind it. We continued our unfinished business toward the summit after a 10-minute break. We had to go down a bit and crossed a huge but relatively flatter snowfield before we could climb up that big hump. Although we called it a snowfield, it would be more appropriate to call it an ice field, which had been sharpened to one direction by the strong wind at night. The temperature was still above the freezing point as long as the blazing Sun was present. The wind in daylight was gentle and not bothersome by any means. I was wearing sunglasses the whole time, but my partner wasn’t. When I took it off from my face for curiosity, the reflection of light from the ice almost blinded my eyes. Climbing up the hump was not any easier, but at least it was not as scary as the previous one. We probably got used to the steep hill. It was physically hard, but not mentally. Yet, it still took us 90 minutes to reach our final destination. At 12:00 p.m. of 10/3/2020, we successfully accomplished our first summit attempt of Mt. Adams at an elevation of 12,276 feet. Standing on top of the second-highest mountain in Washington, we were granted an amazing 365-degree view of the landscape across southern Washington and northern Oregon. It featured a direct lookout of Mt. Rainer 50 miles away, Mt. St. Helens 30 miles away, and Mt. Hood 55 miles away. All of these majestic mountains, Rainer (14,411’), Adams (12,276’), and Hood (11,250’), have the same age of 500,000 years on the Cascade Range. Mt. St Helens (8,366’) however is a baby sister amount all, which is only 40,000-year-old. On top of Mt. Adams, there WAS a shelter. Now it collapsed and had been abandoned, yet it has become a character which climbers would like to take a photo with to show their success of summit attempt. Standing on the peak, at that moment our excitement was indescribable, and the view left us speechless. Yet we know we would become a storyteller to proudly share our experience over and over again. I would really like to end my writing here with a happy ending; however, there were more to come. Mt. Adams is an aggressive mountain. It reveals its dark side in an unexpected way. At 2 o’clock in the afternoon, we packed up our stuff and started to climb down. It had been a satisfying journey, and we could not wait to bring this experience home… only if we made it alive. Unlike Mt. Rainer, the tail in Mt. Adams is unmaintained with scrambles; much of the way with no trail at all. We had to rely on our pre-downloaded phone map and people’s footprints all the way to the summit. The weather in a high mountain was tricky as well as the trail. The warm weather during the day melted the snow and ice quickly, which led to the rocky terrain expose. The tread was extremely loose and could slide out underfoot in steep sections. As the footprints seemed not visible anymore, we completely relied on our phone map. That was our first mistake. The GPS is never 100% precise to locate a single point, and the discrepancy may occur. When climbing down, we noticed the steepness had increased. Later on, the steepness had reached the point I felt like climbing down a cliff, and I was not wrong. However, we did not question the direction we were heading. We have been thinking that going down was what we need to do first. I tried to stay on snowfields as much as I can because a rocky terrain with loose soil made everything slide. Falling rock is an enemy for a climber. The gravity made the momentum of a rock so great that it can easily knock off a climber from behind or head on the face. The Semi-melted ice field became so loose too, that even shoes with microspikes had a hard time to grip the surface with a 50 to 70-degree of steepness. I had to keep my ice axe handy in my descent of routes to prevent myself from uncontrolled glissade. Yet, the scariest thing still happened. My partner missed a step and started to slide down at an unmanageable speed. It occurred in one-half of a heartbeat, and the ice axe was no longer held in hands. With that steepness, sliding down on an ice field was just as scary as falling off a cliff. The scary part is not sliding, but what ends up from sliding at a significant speed. My partner hit a rock and stopped. Fortunately, the body part which absorbed the great momentum was the buttocks. They hurt a lot but no broken bones nor open wounds. Yet, this traumatic moment made the fear be hidden no longer but came out as tears. At 5 p.m., we were still high up far from Lunch Counter. We decided to get off the ice field and try to climb down via a rocky terrain. A rocky terrain was just as dangerous as ice fields, to be honest. We were unable to stay still but slid out underfoot whenever we tried to have a better grip. We had to learn how to “surf on the rock” in the middle of the cliff to keep moving down safely. By that time, Mt. Hood was no longer in the center of our view, which was actually on our left. As the sun was setting to the Cascade Range, we started to feel panic. We spent 5 hours climbing down, yet we were still far from where we would like to be. We had consumed all of the water and only had limited food left. We could not get any faster on those sliding rocks without risking our lives. It was impossible to climb up and extremely dangerous to climb down; standing still on sliding rocks was not one of the options, either. At 7 p.m., we decided to take a break on a relatively stable rock and eat what we have; we charged our phone as it had been out of battery since the incident. Then we finally found out that we were off; one mile off from the right trail horizontally. One mile sounds short, yet it was considered as a suicide mission to climb horizontally across several cliffs in the dark, especially on the loose terrain with near-vertical steepness. Plus, we had exhausted our water, food, energy, concentration, and flashlight. There were not enough clothes to keep us warm at night. Considering the odd did not favor our side, I made the decision to call for rescue. We hesitated a bit because we had no experience of calling 911. We are concerned about any hassle we may get into after the police department involves. Yet, we still made the call because this may be our last chance to call for help when both of us are still fine. It would be too late to call or no more chance to call when we encounter another horrible incident, which is extremely likely. One bar of phone signal was considered as a lifesaver, especially when we stuck on an elevation of 10,000 feet. Yet, the rescue team was not as fast as most people thought. Most of the rescue team do not own a helicopter. If the rescue request is considered life or death, they borrow a helicopter from US Army after approval of the urgent request, which may take as long as 2 to 3 hours (if gets approved). Meanwhile, the rescue operation also sent the ground team, which may take 3 hours to arrive at the trailhead and 4 hours to climb up to where we were. As a long night came along, the temperature was dropping 2-4 degrees every 30 minutes. At 11 p.m., it had dropped below the freezing point. Our bodies started to have a hard time keeping our lower extremities warm, especially our feet which were soaking wet due to sliding on the snow. We did not feel hungry, yet we experienced fatigue. Because of lack of sleep in the past 20-ish hours and losing significant amounts of heat, our bodies started shutting down. We were hoping for the best that US Army could approve our rescue request and send an aeromedical evacuation crew promptly because we did not think our body could make it for the ground team to arrive at 5 in the morning. As the rescue team did their best to make the approval process as less time-consuming as possible, the helicopter arrived at our location at midnight. While lifting up vertically from a truncated spur facing toward the rocky terrain, the view was supposed to get slightly extended and a farther outlook should be in sight. However, all we could see was a WALL in front of us all the way until we were over the peak. We were shocked that we literally stood, climbed, and slid on a near-vertical cliff in the past 10 hours. We were transported to VMM Hospital in Yakima, WA. Luckily, we were in stable condition with normal vitals except for mild hyperthermia. We were discharged from the ER within an hour after our arrival. We stayed in the lobby till the dawn ended this most frightening and longest night in our lives. Mountaineering could be a risky and dangerous activity, which requires adequate knowledge, sufficient experience, and proper gear. To climb a well-preserved unmaintained mountain, like Mt. Adams, a mistake could cost a life. This time, we definitely need more time to embrace and digest the trauma before attempting our next mountaineering. Yet, we are still proud to say that we summited Mt. Adams at its majestic elevation of 12,276 feet! We would never say it is easy, as it taught us a life lesson in the hardest way. 10/3/20